Introduction:

Mangesh Niranjan Patankar, heads the local agriculture underwriting team at the India branch of Swiss Re. He is responsible for managing the Indian agriculture reinsurance business. Prior to this, Mangesh served as an Underwriter in the Agriculture team in Singapore, where he worked on structuring, pricing, and underwriting crop and livestock reinsurance products for markets in South Asia and Philippines.

Q: The PMFBY (Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana) has been in India for five years. What have been the scheme’s most significant achievements in India?

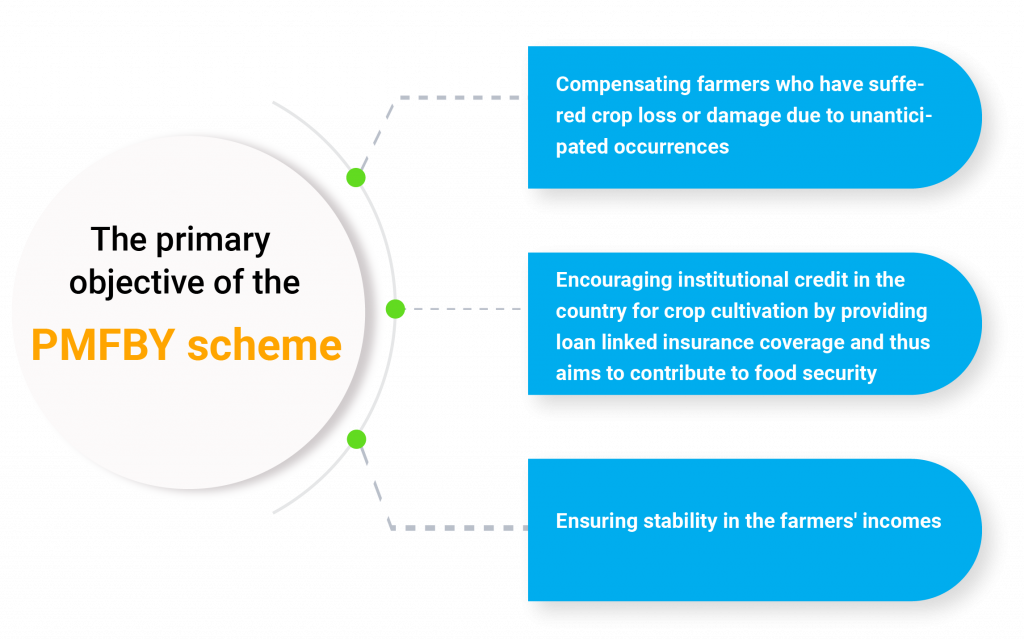

Mangesh Niranjan Patankar The primary objective of the PMFBY scheme is to help farmers produce more sustainably by:

As the products are index-based and reflect the status of the farm productivity for a larger administrative unit, it also encourages the individual farmers to see to it that they increase their individual, farm-specific productivity through the use of new and contemporary farming techniques.

There have been similar products in the past, like the National Agriculture Insurance Scheme (NAIS) and Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (MNAIS). Still, the traction that PMFBY has gained is incredible.

Compared to NAIS – which existed until 2015, PMFBY provides several additional features to take care of localised perils, post-harvest losses and mid-season disasters facing farming communities. In the inauguration year, the scheme received quite an encouraging response from most of the states. The sum insured, crops insured, and farmers’ participation increased, thanks to the heavy subsidy commitments by the Centre and State. Compared to MNAIS – which remained a relatively smaller scheme due to co-existence with NAIS – the PMFBY scheme has successfully adopted technological interventions such as mobile-based yield data collection, satellite data-based smart sampling, a dedicated scheme portal for enrolment, subsidy handling and claim settlement. Moreover, as against MNAIS, where the claims disbursed under the non-yield index components were minimal, we have seen much higher benefits disbursed under PMFBY. Key examples include post-harvest losses in Maharashtra in 2019, sowing failure losses in Rajasthan in 2018, localised calamity losses in Haryana and Odisha in various years.

One definite success for the government is putting the PMFBY plan into action and actively marketing it. There have been some critiques, but that too has a beneficial impact as some of those are addressed under the subsequent revisions of the scheme.

The key focus remains on fairness in subscription, as well as claims assessment. I would like to point out that a mandatory AADHAAR (national identification number) linkage has been widely implemented since 2017. The second point is land record integration, which is dependent on the state’s infrastructure, and thus the success of finding genuine beneficiaries varies from state to state. However, the concept of area correction factors largely helps in curbing the problem of oversubscription.

As far as fairness in claims is concerned, there is a detailed protocol for crop sowing failure, post-harvest failures, and mid-season adversities. For the yield index component, the government is developing smart sampling methodologies for the major crops in various states. Swiss Re worked on this concept way back in 2013, along with the Maharashtra government, CRIDA, the Agriculture Insurance Company of India and a private ag-tech firm. However, it has taken time to translate such efforts into government policies. I am glad to say that the Government of Orissa has started putting this concept into practice since 2018, and it has been an enormous success. Overall, we have seen increased ground monitoring by insurers, rationalisation, digitisation and improved accuracy of crop cutting experiments.

Q: What are the critical gaps in the PMFBY that technology has been able to fill, and which ones remain?

Mangesh: In 2016, when the PMFBY era began, despite very well-articulated operational guidelines, many uncertainties prevailed around the implementation aspects. However, the stakeholders were determined to ensure that the guidelines are practised the intended way, and technological intervention significantly enables that. For example, AADHAAR linkage and land record integration have made a difference. Even more important is the widespread use of technology to sample CCE locations and record their outcomes. Whereas smart sampling as a concept has existed for a long time, PMFBY perhaps created the urge to translate it into practice. Central government institutions like MNCFC, NRSC and individual state governments are heavily involved in instrumentalising this on the ground.

The Central Government has attempted to roll out a simple smartphone app handed to local agriculture authorities to record CCE outcomes in several states. Additionally, a counter application is provided to the insurance companies or their vendors to check the findings. That was the feature that prior systems lacked, maybe because smartphones were not widely available at that time. It is a progressive step, and the best thing is that these applications are simple to comprehend, and anyone with a basic understanding of smartphones can operate them. Although not all the CCEs are being conducted using these apps, the uptake is phenomenal over the past three years. Overall, the behavioural changes around the topic of yield data recording is a major victory of the PMFBY scheme.

We also see increased use of social media for advertising the benefits and performance of the scheme. Government, as well as insurers, are seen adopting such digital marketing techniques.

Q: Do you see any significant gaps in PMFBY that technology can bridge, such as claim assessment, underwriting, etc., where technology can make a difference?

Mangesh: Technological interventions have played a key role as far as distribution and claims assessment is concerned. As yield index remains the predominant component of PMFBY, and most insurers have been using merely 10 to 15 years of yield data for their underwriting decisions, it is important to look beyond this period and dig deep to understand the unseen frequency of major weather events. For this purpose, we can use satellite-based weather, soil moisture and vegetation datasets. This gives a better idea of the return periods of the calamities – e.g., what is the possibility of a cyclonic storm striking a particular district in Tamil Nadu? How many back-to-back drought events can occur in Maharashtra in one century? We need this know-how built in the underwriting decision-making systems of the insurers and among the states implementing this scheme as the product prices can be driven by these unseen events.

Let’s also not forget about the issues that manually recorded yield datasets have in the country. The validation of such datasets in the past – especially pre-2015 when PMFBY did not exist – has been weaker, and further, the measurement of such datasets may not have happened at the level where the scheme wants it to be. This poses challenges around the correctness of such datasets.

If we think more broadly, going beyond the manually recorded yield-based insurance, we see immense product structuring opportunities using similar datasets. An example is the recent adoption of the Crop Health Factor by the West Bengal Government. The idea is to design an alternative to yield index and reflect crop stress using objective parameters derived from optical and radar remote sensing datasets. Whereas such products need time to stabilise and a lot of commitment from the stakeholders for ground-truthing, once the design gets established, the underwriting and claim assessment can happen much more quickly and transparently.

Q: Do you think the rise of Agtech’s in India will open up opportunities for new insurance product design that caters to farmers’ and agricultural cooperatives’ more hyperlocal needs?

Mangesh: Certainly! Hyper-localisation is already happening as the existing crop insurance speaks about implementation at the Gram Panchayat level, which was unheard of a few years back. However, even after implementing the crop insurance at this level, we hear deviations in farmer specific experiences and the representative yield index. It would be better to provide compensation to farmers who have suffered losses on their land. This can only happen if we have excellent farmers and land records database

With the rise of ag-techs, I am sure we can start inching towards a farm level insurance product. However, this journey won’t be easy. I do not doubt the abilities of ag-techs in supporting such products, but the insurance industry needs time to develop suitable infrastructures to process a significant amount of data. We need appropriate skillsets and data management systems. Moreover, not all states have digitised land records and insurers cannot handle this part of the journey.

Q: In recent years, frequently occurring catastrophic events have become the new normal, and insurance is a key component that must be there. What influence has the reinsurance business had in South Asia and Southeast Asia, where insurance penetration is significantly lower?

Mangesh: We have experienced unparalleled events in recent years, such as the Tamil Nadu drought (2016) and the Madhya Pradesh floods (2019), which have about a one hundred-year return period. The worst part is that we are witnessing more of these events – indicating a need to revise the assumptions around such return periods. The 2021 Europe floods are a classic example.

This warrants continuous updates of the premium rates and, thus, more investments from the government in terms of premium subsidies. Insurance penetration remains a concern for South and South-Eastern Asian countries, but what is more worrisome is the skewed distribution of subscription rates across the countries.

We need a serious discussion around agriculture insurance needs at the national level in several countries in these regions to institutionalise comprehensive risk-transfer mechanisms similar to PMFBY in India or the Thai Rice scheme in Thailand. As far as the financial risk-taking capabilities are concerned, the reinsurance industry is relatively resilient to absorb these risks because of the allocation of capital to risks spread across the globe. Thus, the resilience of domestic insurance companies would be largely dependent on their reinsurance purchase mechanism. Such a resilient primary insurance market can significantly impact the risk-taking abilities at the domestic level, which would mean more insurance penetration in such countries. Apart from reinsurance, insurance-linked securities can be considered an alternative, although we haven’t yet seen this in the region.

Q: What do you believe are the essential technologies that insurers should invest in to accomplish their objectives?

Mangesh: It’s surprising that in India, the profitability of primary insurance companies is dependent on investment income over underwriting income. This implies that the premiums they receive are insufficient to cover the claims they pay out in any given year. Insurers, in my opinion, need more vital collaboration with the global reinsurance industry to further improve the underwriting and exposure management models in the business.

In claim management, new yield-based model products will emerge over the years, which will largely automate the processes.

Such transition needs upgrading skillsets of the current underwriters, claim managers and surveyors and more investments in data crunching and data management abilities of every insurer.

This article was originally published in The SatSure Newsletter [TSNL]